Growing up in Cebu during my childhood, I witnessed the gradual transformation of our island's landscape. The mountains that once stood proudly covered in lush greenery began showing patches of gray as timber cutting, quarrying, and development of upscale subdivisions took their toll. Yet during those years, major storms remained rare occurrences that people would remember for decades.

The Era of Black Swans Turns White

I vividly recall Typhoon Ruping in 1990, a name that still resonates in every Cebuano household old enough to remember its devastation. Back then, such powerful storms represented what economists call "black swans" - violent, improbable events that left permanent marks on our collective memory. Today, that reality has fundamentally changed. What were once exceptional disasters have become regular occurrences in our lives.

The black swans have turned white. Typhoon Tino and similar storms now sweep through Cebu with alarming frequency, reopening the island's wounds repeatedly. Streets transform into raging rivers, rivers become destructive walls of water, and the sea returns to claim what the denuded mountains can no longer hold back.

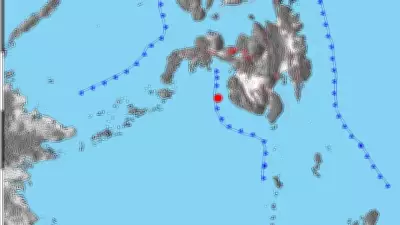

Cebu's Geographical Vulnerability

Cebu's geography has always presented both its greatest beauty and its most significant burden. Our island stretches long and narrow, rising sharply in the center and descending quickly to the sea on both sides - essentially functioning like a roof with two gutters. When heavy rains come, the water has little distance to travel from mountain to coast, leaving minimal time for preparation and no room for the water to dissipate naturally.

As children, we proudly boasted that in Cebu, you could drive from the mountains to the sea in under an hour. We saw this as evidence of our island's charm and convenience. We failed to recognize this proximity as a double-edged sword that would eventually leave us with nowhere to escape when the heavens opened with increasing intensity.

The Ecological Unraveling

During my youth, the forest canopy still served as nature's brake system, slowing the descent of rainwater. The soil acted like a massive sponge, and our rivers could breathe properly. However, decades of logging, quarrying, and dolomite extraction systematically stripped away this natural protection. Areas that once required six hours of continuous rain to flood now submerge within a single hour. Our island, which naturally absorbed water, has been forced to shed it rapidly.

The rain itself has undergone a dramatic transformation. A warmer planet means heavier skies, with each degree of temperature increase allowing the atmosphere to hold seven percent more moisture. The clouds that once brought gentle showers now dump entire lakes worth of water in a single day. Even cities with billion-dollar flood defenses like New Orleans and inland urban centers like Knoxville have found themselves overwhelmed by rainfall too intense to manage. If the best engineering solutions cannot protect these places, what hope does a narrow island with bare mountains and paved coasts truly have?

Beyond Political Blame Games

In the aftermath of Typhoon Tino, public discourse quickly devolved into political finger-pointing about flood control projects - who built them, who failed to build them, and who potentially profited from them. However, this perspective misses the fundamental truth that floods follow physics, not party lines. Cebu's tragedy cannot be explained by drainage budgets alone. The real story lies in the accumulation of years of ecological neglect, poor urban planning, and the dangerous illusion that concrete alone can solve every environmental challenge.

The danger of this short-sighted approach is that it blinds us to the deeper ecological wound. Flood control measures might temporarily slow the water's progress, but they cannot heal the land itself. The real solution begins upstream through comprehensive reforestation, watershed rehabilitation, mangrove protection, and honest governance that prioritizes long-term resilience over ribbon-cutting ceremonies. This demands the courage to think beyond single budget cycles, to value substantive formation over optical achievements, and to measure success not by kilometers of concrete canals but by hours of peace enjoyed after the rain stops.

The Shrinking Silence Between Storms

During my youth, a major storm became a story told for years, with generations defined by the typhoons that shaped their experiences. Somewhere between Ruping in 1990 and Tino in recent years, time itself seemed to disappear. The intervals between disasters have dramatically shortened. The land no longer has sufficient time to dry properly, the rivers cannot clear themselves completely, and the people lack adequate time to heal emotionally and rebuild physically. This represents the true meaning of climate change for vulnerable places like Cebu - not just stronger storms, but critically shorter silences between them.

Beneath the physical destruction lies a spiritual grief that affects us all. When the natural rhythm of the land breaks, something within us breaks as well. The rain no longer feels like a blessing, and the mountains no longer appear as protective guardians. Yet even amid the ruins, grace continues to murmur quietly. The memory of a greener, healthier Cebu should not be dismissed as mere nostalgia - it serves as prophecy. It reminds us that what was once alive and thriving can live again if we find the courage and commitment to restore it.

If Ruping represented the black swan of my childhood, then perhaps Tino can become our bright sign - the storm that finally teaches us what we refused to learn during calm periods. The only sustainable way to stop drowning is to remember that true safety once grew not from mastery over nature, but from living in harmony with it.