The ambitious New Manila International Airport project in Bulacan, promoted as a pillar of nation-building, is casting a long shadow of environmental risk over millions of residents in Central Luzon. Beneath the promise of progress lies a stark reality: the construction of a massive 12,000-hectare infrastructure on a critical hydrological system.

A Project of Massive Scale and Hidden Danger

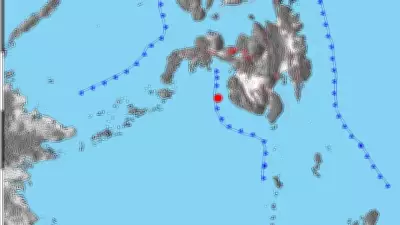

Official narratives often highlight the 2,500-hectare "aerocity" but frequently omit the accompanying 9,500-hectare economic zone. Combined, this 12,000-hectare footprint consumes wetlands, mangrove forests, and natural floodplains in Bulacan. The site is strategically precarious, located where three major rivers converge—a deltaic area that naturally sinks and serves as the primary drainage basin for Central Luzon into Manila Bay.

This location choice contradicts a science-backed plan from over a decade ago. In 2011, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) recommended expanding Clark International Airport and developing Sangley Point in Cavite. The Sangley option was noted for its stable ground, minimal need for reclamation, and significantly lower storm surge risk, presenting a more sustainable long-term solution for the region.

Political Expediency Over Environmental Logic

The project's approval timeline reveals a shift in priorities. The Aquino administration in 2013 initially rejected unsolicited proposals, cautioning against loss of transparency. However, by 2017, the Duterte administration embraced San Miguel Corporation's proposal, heavily influenced by its "zero cost to government" promise.

This framing led to swift legal maneuvers. By labeling the project as of "national significance" and "strategic infrastructure," it bypassed standard scrutiny. Laws such as Republic Act 11506 and RA 11999 granted it national status, effectively overriding local zoning laws, municipal land use plans, and critical coastal protection mandates. Floodplain regulations were weakened, and the Supreme Court's directive to rehabilitate Manila Bay was sidelined.

Real Consequences and a Path for Accountability

The environmental impact is no longer theoretical. Communities in Bulacan and Pampanga are experiencing longer and more severe floods. The CAMANAVA area (Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas, Valenzuela) faces a future of elevated water levels. On the ground, farms are deteriorating, fishponds are collapsing, mangroves are receding, and groundwater is turning saline.

Despite the challenges, legal avenues for oversight remain. Under RA 11999, the Provincial Government of Bulacan holds supervisory powers to ensure the project's development plans align with provincial ecological and flood control standards. It can withhold local permits where legally possible and escalate issues of non-compliance to national agencies.

Transparency is key to shifting the narrative. Public disclosure of audit results, compliance reports, compensation policies, and a clear grievance process can move the focus from corporate promises to measurable impacts. While the project promotes job creation, employment cannot restore saline aquifers, revive drowned fields, or rebalance a disrupted hydrology.

The choice between spectacle and stewardship is clear. The alternatives—Clark and Sangley—align with scientific evidence and offer capacity without sacrificing a delta's essential life-sustaining functions. As history judges these decisions, the need for leadership that respects science, tells the truth, and protects land and water from the burden of deception has never been more urgent.