A festive spirit blankets Cebu City today, marking an event of profound national significance: the arrival of Christianity in the Philippines. This celebration, however, rests on a historical narrative that is far more complex and contested than the traditional story suggests.

The Miraculous Sign and a Conquest Justified

According to letters from Miguel Lopez de Legazpi to King Philip II in 1565, the Spanish explorer was uncertain about settling in Cebu. The decision was cemented when one of his soldiers discovered an image of the Santo Niño. Legazpi interpreted this as a divine sign that God had awaited them on the islands. This discovery provided a powerful justification for the subsequent brutal conquest and was later used to legitimize over three centuries of Spanish rule.

Historians have long assumed this image was the same one given by Ferdinand Magellan to "Queen" Juana in 1521. Spanish officials viewed the rediscovery as a heavenly mandate to continue Magellan's work. Yet, this prevailing assumption is now under scholarly scrutiny.

Questioning the Established Narrative

In her book Saints of Resistance, Princeton University professor Christina H. Lee challenges the direct link between Magellan's gift and Legazpi's find. She argues that Legazpi himself may have been unaware of the 1521 story. Connecting these two events—Pigafetta's account and Legazpi's report—might be an undue simplification. Other foreign sources, like the Portuguese who attacked Bohol around 1563, could have been the origin.

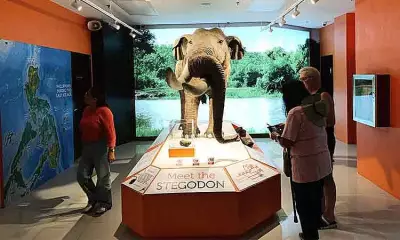

More intriguing is the claim from the natives themselves. Fray Gaspar de San Agustin recorded in Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas that the people of Cebu asserted the Santo Niño had been with them "since time immemorial." This created an early contestation over the image's ownership and origin, highlighting a clash of perspectives from the very beginning.

Indigenizing the Faith: A Filipino Response

The Spanish accounts often judged native practices harshly. When "King" Tupas and his men visited, they admired the Spanish veneration of the Child-God. The Spaniards accused the Cebuanos of honoring the Santo Niño merely as another diwata (spirit). But what if this was a gross misinterpretation? The negative judgment likely stemmed from a conqueror's perspective and a Eurocentric bias that their worship was the only correct form.

If the original Spanish missionaries witnessed today's Sinulog festival, with its passionate shouts of "Pit Señor!" and rhythmic dance, they might protest in horror. This illustrates a core truth: the Filipino acceptance of Christianity was not passive. It was an active process of choosing which elements to embrace and how to integrate them into local culture. Christianization was not a simple transplant of Hispanic faith; it was a creative indigenization.

This pattern of localization continued with other devotions. The natives initially resisted the Hispanic Our Lady of the Rosary (La Naval de Manila), seen as the colonizers' patron. In contrast, they readily embraced Our Lady of Antipolo, transforming her into a local advocate. To this day, communities create their own narratives, like the dark-skinned Birhen sa Regla who swims in Mactan or the fair-skinned Our Lady of Guadalupe protected by mango trees.

The Spanish did not merely Christianize the natives. Our ancestors, and we continue today, to nativize Christianity. What was received was a Europeanized faith, but what has flourished is a universal, not uniform, Filipino expression of belief. The story of the Santo Niño is, therefore, not just a tale of discovery but a foundational chapter in the ongoing Filipino journey of making faith their own.