In a deeply personal reflection from Lindogon, Sibonga, Cebu, a writer grapples with the raw pain of heartbreak, finding an uncanny mirror to their own suffering in a 19th-century Russian literary classic. The piece, dated January 7, 2026, uses Fyodor Dostoyevsky's short story "White Nights" as a lens to examine the universal agony of being someone's second choice.

A Literary Mirror to Modern Heartache

The author begins by pondering the choices of Nastenka, the heroine from Dostoyevsky's "White Nights." In the story, Nastenka waits a year for her first love to return, only to be comforted during her despair by a new dreamer she meets on a bridge. When her first love finally returns, she leaves the dreamer, who had fallen deeply for her. The writer questions why Nastenka chose her first love over the devoted narrator, stating they would have given the victory to the dreamer. This literary analysis sets the stage for a painful personal revelation.

When Fiction Becomes Painful Reality

The essay takes a sharp turn from literary critique to confessional. The author reveals they do not share Nastenka's fate, nor are they like her first love. Instead, they profoundly identify with the dreamer, the storyteller who loved Nastenka but was ultimately abandoned. This connection is rooted in a recent, devastating personal experience. The writer's own relationship ended abruptly after just three weeks when their partner confessed to reconnecting with a former love from five years prior, expressing a desire to rekindle that old flame.

The moment of breakup is described with visceral clarity. The partner cried, their tears seeming meant to soften the writer's heart into granting freedom. The most crushing blow came with the partner's comparison: "Why isn't he like you? Why? He is not as good as you, even though I love him more than you." The writer was left with the helpless, unanswered questions: Why not choose me? Why is he heavier than me?

The Unwinnable Battle Against a Ghost

The reflection delves into the core issue of entering a new relationship while still haunted by a past love. The author concludes that while one may never fully forget a first love, a strong heart should be able to choose the present person steadfastly, regardless of who returns. Their final words to their departing partner were a resigned acknowledgment: "Even if I were the most righteous person in the whole world, if you do not love me, it is pointless." The partner left with a simple apology, leaving the writer whispering their name in sorrow.

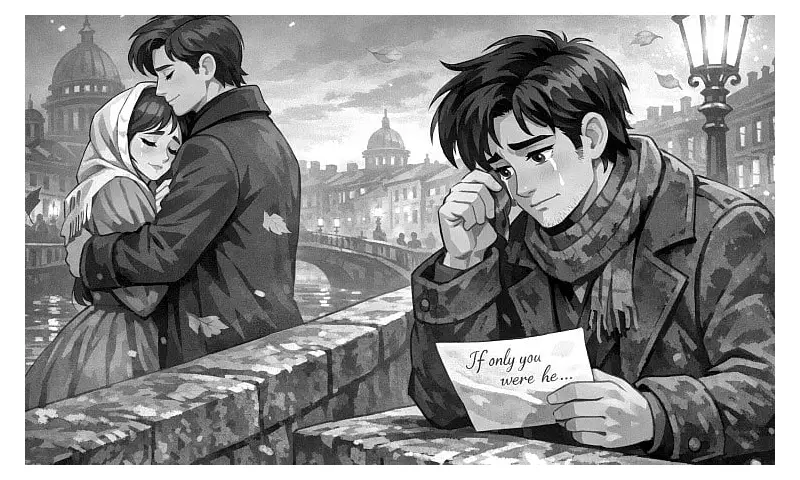

The essay returns to "White Nights," citing the heartbreaking line from Nastenka's letter to the dreamer that shattered the author's own heart: "If only I could love you both at the same time! Oh, if only you were he!" The author laments that in such love triangles, there is always a winner and a heart that is forsaken. The losing heart is at a perpetual disadvantage because it will remember the person it loved for its entire life.

In a final, somber parallel, the writer from Sibonga, Cebu, accepts a fate similar to Dostoyevsky's dreamer: from the very beginning, they were only a fleeting, close moment in the heart of their beloved, never the final destination. The piece stands as a powerful testament to how classic literature can frame and give voice to our most contemporary and personal pains.