A stark contrast between the lavish perks of lawmakers and the daily struggle of ordinary Filipinos has ignited public anger, raising fundamental questions about equity and governance in the country.

Congressional Perks Amid Widespread Hardship

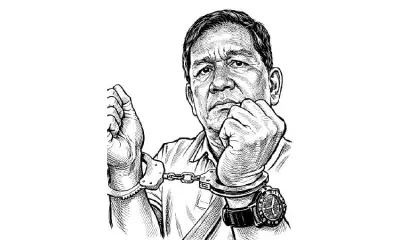

The controversy was fueled by revelations from within the House of Representatives itself. Congressmen Ronnie Puno, Kiko Barzaga, and Leandro Leviste disclosed practices that they found difficult to stomach among their colleagues. According to their accounts, members of the House receive additional bonuses every time they go on breaks, such as for Christmas and the Lenten season.

These bonuses come on top of their already substantial monthly salary exceeding three hundred thousand pesos, plus other allowances and benefits. This disclosure has led to widespread criticism and calls for accountability, with many asking why no major political figures have been held to account.

The Pinoy Worker's Dire Reality

This reality stands in brutal opposition to the experience of the average Filipino worker. The current daily minimum wage is around seven hundred pesos, a figure that is utterly mismatched against the multi-million-peso takes of many politicians. For countless families, life has been reduced to mere survival.

The situation is a far cry from earlier decades. The author recalls a childhood where a daily allowance of five centavos was sufficient for a boiled sweet potato and a hopiang mungo, with water from the school pump. A ten-centavo allowance was considered luxury, enough for a special halo-halo and a mamon. The daily wage for ordinary workers then was four pesos, which could meet the basic needs of a family of five to eight.

Travel and luxury were for the few. A round-trip bus ticket from Angeles to Manila cost eighty-five centavos on non-air-conditioned buses like La Mallorca Pambusco or Philippine Rabbit. A more affordable option was the government-run Philippine National Railway. Entertainment was simple and cheap; a child's movie ticket in Angeles City was fifteen centavos, and a plate of pancit luglog in San Nicolas Public Market cost ten centavos.

From Affordable Education to Unaffordable Living

The affordability extended to education. The author's matriculation fee for a whole semester at the University of Santo Tomas' College of Philosophy and Letters was one hundred five pesos. Board and lodging in Manila's university belt could be had for forty pesos a month, with friends sharing a bed space for as little as fifty pesos monthly, split six ways.

Today, that sense of affordability has vanished. As the author laments, a current salary can only buy basics like noodles and sardines, with even dried fish becoming expensive. The government, particularly the majority in the House of Representatives, has shown inflexibility in passing a law for a significant wage hike. Regional wage boards issue increases that fail to address the workers' desperate pleas.

The final insult for many came from Trade Secretary Cristina Roque, who claimed that a family of four could enjoy a Noche Buena last Christmas with just five hundred pesos—a statement that has been met with disbelief and fury from a public drowning in the high cost of basic commodities.

The narrative paints a picture of two Philippines: one where political privilege is institutionalized through bonuses and high pay, and another where ordinary citizens fight a daily battle for dignity against stagnant wages and relentless inflation.